Rounding the nook close to the village of Rodanthe, there’s a stretch of freeway generally known as the S-Curves due to its twisting loops and turns. It’s, by nearly any measure, some of the weak sections of roadway in North Carolina, if not the nation. Years in the past, freeway officers erected an enormous dike right here with 2,200 sandbags — every bag was 15 toes lengthy, two toes tall, and 5 toes broad — after which buried the dike in much more sand in an effort to maintain the ocean at bay and the freeway, generally known as NC 12, open.

It didn’t work, or a minimum of it didn’t work as hoped. The Atlantic Ocean continued to pummel the towering synthetic dune, crashing excessive, tearing aside sandbags, and flooding the freeway — closing the one entry on and off of the decrease Outer Banks for days and typically weeks.

Following every storm, the North Carolina Division of Transportation (DOT) despatched in bulldozers and graders to rebuild the sand dike and patch the highway, solely to look at the following storm undo its work. “It’s just like the Siege of Troy,” stated native biologist Mike Bryant. “It simply goes on and on.”

Bryant managed the close by Pea Island Nationwide Wildlife Refuge — a sprawling, 13-mile-long sanctuary that pulls tundra swans, Canadian geese, and 400 different species of migrating birds for twenty years. He estimated that he spent 60 p.c of his time on NC 12, together with issuing permits to state and federal engineers to restore storm harm and severely eroding sand dunes. “It felt exhausting at occasions,” he stated.

U.S. coastal resorts from Cape Cod to Galveston face unprecedented challenges as shorelines slim and floodwaters inch nearer.

In a single sense, NC 12 stands as a metaphor for the risks of constructing something on a extremely dynamic, constantly-shifting barrier island, particularly one which has misplaced a whole bunch of toes of shoreline in locations over the past century and now faces even-larger threats from sea degree rise and extra frequent and highly effective storms associated to local weather change. The dangers aren’t restricted to the Outer Banks, after all. Nationally, U.S. coastal resorts from Cape Cod to Miami to Galveston face unprecedented and dear challenges as their shorelines slim and floodwaters inch ever-closer to hundreds of thousands of homes, condominiums, and accommodations — over one trillion-dollars-worth of property in all.

Nonetheless, nowhere are the threats extra seen than alongside the famed Outer Banks of North Carolina, the place every summer season a flotilla of SUVs ship keen vacationers, swelling the inhabitants practically tenfold, to over 300,000, whereas additionally fueling a vacationer economic system that helps 1000’s of jobs and generates hundreds of thousands in tax revenues for native governments.

Practically 4 many years in the past, the College of Virginia coastal geologist Robert Dolan, a long-time researcher of barrier islands, wrote that the Outer Banks are “one of many highest natural-hazard danger zones alongside the whole Jap Seaboard of the US.” He cited the Banks’ distinctive geography and dangerous publicity to storms, unstable currents, and percussive winds.

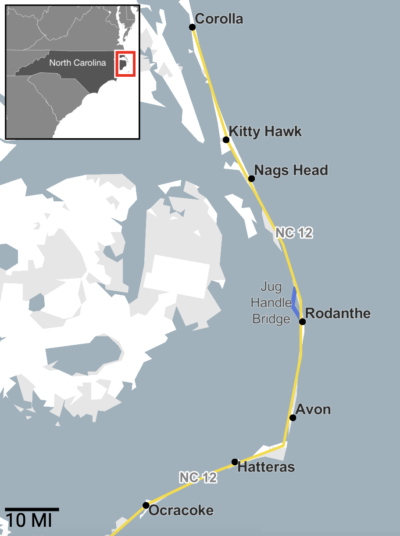

North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

Yale Surroundings 360

Considered from an airplane, the practically 200-mile-long ribbon of islands resembles a baby’s Etch-A-Sketch drawing, skewing north to south for miles, then out of the blue veering east to west close to Hatteras Village, earlier than turning as soon as extra in a southeasterly course. Among the islands are low and slim, only some toes above sea degree, and particularly weak to winter Nor’easters and hurricanes in summers. The nice and cozy waters of the Gulf Stream and colder Labrador Present collide simply miles offshore, creating harmful shoals and a few of the largest waves alongside the East Coast. Over many centuries, scores of inlets have opened and closed on the Outer Banks, whereas the barrier islands have slowly migrated landward as sand has washed throughout shorelines and flats on the oceanside and marshes have expanded alongside the bottom, in response to one federal research.

Regardless of these dangers, builders proceed so as to add billions of {dollars} of actual property, from Corolla within the north to Ocracoke Village within the south, making the Outer Banks the fastest-growing part of the North Carolina coast. Property values have additionally soared to at an all-time excessive. Dare County, which incorporates 1000’s of seashore properties, just lately valued all of its property at practically $18 billion. Whereas the worth of ocean property in smaller Currituck County has ballooned to nearly $5 billion.

“It’s as if nobody cares,” says Danny Sofa, a Dare County Commissioner, actual property agent and typically tour information. “Lots of people have a lot cash they don’t care in regards to the danger.”

Within the final decade alone, DOT has spent practically $80 million {dollars} to maintain hazard-prone NC 12 open for the year-round residents of the decrease Outer Banks. That features rebuilding the S-Curves three totally different occasions, however doesn’t embrace the price of three new bridges wanted to traverse inlets opened by storms or to bypass the quickly eroding shoreline. Collectively, the bridges push the price of sustaining NC 12 to a couple of half-billion {dollars}.

Areas of the Outer Banks have retreated over 200 toes within the final twenty years and are at present dropping about 13 toes a yr.

Requested if there have been one other freeway as weak as NC 12, Colin Mellor, a DOT environmental specialist, shuffled round a bit earlier than answering: “No, emphatically, is the reply. NC 12 is a poster little one nationwide, if not worldwide,” he stated. “It’s a North Carolina route on a ribbon of sand that jumps out into the ocean.”

This spring, two trip properties within the Commerce Winds Seashores subdivision of Rodanthe crashed into the ocean throughout a storm. One bobbed like a cork within the rioting surf till a wave grabbed ahold of it and smashed it to items. That night movie of the collapse spiraled onto nationwide tv. In a weblog entry, native photographer Michael Halminski wrote that the expertise “jogged my memory of the Depraved Witch getting splashed with water and melting away.”

Cottages have been tumbling into the ocean for so long as people have been constructing alongside the Outer Banks. The distinction now’s that they seem like falling in at a sooner price, and scores of properties at the moment are in danger. Halminski estimates that he’s seen about 50 homes destroyed because the Seventies. Mike Bryant recollects whole rows of trip homes vanishing into the surf in a number of storms. In South Nags Head, on Seagull Drive, a half-dozen seashore homes squatted within the ocean for years till they had been finally bought by the city as a part of a 2015 lawsuit.

In every occasion, the offender was erosion, which seems to be worsening alongside giant stretches of the Outer Banks. Areas of Rodanthe have retreated over 200 toes within the final twenty years, and are at present dropping about 13 toes of seashore per yr, in response to estimates by the Nationwide Park Service, which manages the Cape Hatteras Nationwide Seashore. Michael Flynn, an NPS scientist, likened the erosion to a checkbook overdraft, with not sufficient sand to guard the homes. “Now, with sea degree rise, it appears to be getting worse,” he stated, “permitting lesser-intensity storm waves to run up the seashore.”

Dare County, which incorporates Rodanthe, just lately tagged practically 20 seashore homes close to the Commerce Winds subdivision as unsuitable to be used due to issues starting from broken septic techniques to wobbly pilings and damaged steps. However the county lacks the authorized authority to sentence the homes and doesn’t have a fund to purchase dangerous properties. Even when it did, it’s unlikely many house owners would retreat, “which nobody desires to do,” stated Bobby Outten, the county supervisor.

That’s to not say, Dare County doesn’t observe a unique kind of retreat. “It’s a Darwinian type of retreat,” says Danny Sofa. “Homes fall in one by one.”

Barrier islands are all the time in movement, rising and shrinking, relying on sea degree, wind course, storm surge, and different elements. In that sense, erosion is a pure phenomenon and solely turns into an issue when people construct too near the water after which attempt to maintain a line that nature by no means meant to carry.

Pumping sand from dredges is simply a short lived resolution, as highly effective storms can gouge a man-made seashore in simply hours.

That is kind of the state of affairs of the Outer Banks and scores of different barrier islands up and down the East and Gulf coasts. A land growth that started right here within the Fifties has added 1000’s of second properties alongside the oceanfront and sounds, even because the shorelines and marshes are washing away. Property house owners and politicians insist that there’s an excessive amount of cash at stake to stroll away now. Certainly, the windfall from the seashores has helped to remodel these North Carolina counties from poor and rural outposts into two of the state’s richest and fastest-growing areas, with property on the Outer Banks accounting for 60 p.c of the tax revenues of Dare and Currituck counties.

“The truth is we rely on tourism, and nobody desires to present that up,” says Sofa. “So, what we’ve to do is to learn to dwell smarter and adapt to the modifications.”

A method Dare County is adapting is by embracing a multimillion-dollar plan to replenish its eroding seashores with hundreds of thousands of yards of sand pumped from dredges positioned offshore. The sand helps present some safety and retains the vacationers pleased. However sand is simply a short lived resolution, and highly effective Nor’easters and hurricanes can gouge a man-made seashore in simply hours.

Flood harm on NC 12 in Rodanthe, North Carolina following Hurricane Irene in August 2011.

Ted Richardson / Bloomberg by way of Getty Photographs

All of which suggests, as soon as you start to pump sand, you just about commit to maintain pumping, a lesson the city of Nags Head has discovered. This yr, the favored resort is embarking on its third spherical of seashore repairs since 2011, when it initially pumped practically 5 million cubic yards of sand onto its seashores at a price of $36 million. Hurricanes in 2018 and 2019 swept away a lot of that sand, and this month the city started pumping sand once more alongside 4.5 miles of shoreline at a price of practically $14 million. In the meantime, the Dare County villages of Duck, Southern Shores, Kitty Hawk, Kill, Satan Hills, Avon and Buxton additionally will probably be pumping sand by this fall.

One group that isn’t getting sand is Rodanthe. Which will appear counterintuitive, however there may be an evidence. The group is getting a bridge as an alternative, constructed within the Pamlico Sound behind the barrier island and increasing 2.4 miles to the southern finish of the Pea Island Nationwide Wildlife Refuge. Constructed at a price of $155 million (80 p.c federally funded), the Jug Deal with Bridge bypasses the extremely erosive S-Curves space of NC 12 and may eradicate DOT consistently having to rebuild the freeway. In reality, that stretch of highway is slated to be torn up this fall, permitting the ocean to as soon as once more wash over the sand and marsh, restoring the world to its pure type.

Final yr, Dare County created the NC 12 Job Drive to review methods to guard its endangered freeway. The group consists of representatives from federal and state businesses and is updating stories accomplished by earlier research teams. “There have been a number of activity forces referred to as no matter they had been referred to as and a number of stories over time,” stated county supervisor Bobby Outten. “Frankly, the problems and sizzling spots haven’t modified all that a lot. What has occurred is that the chance degree or the menace degree has elevated some.”

“They’re making an attempt to protect a coastal economic system constructed on a pile of shifting sand,” says a geologist who studied the Outer Banks.

Within the early 2000s, one group unanimously beneficial constructing a 17-mile-long bridge within the Pamlico Sound bypassing all of Pea Island and several other further sizzling spots alongside NC 12. However the plan collapsed after native politicians objected, saying the lengthy bridge would make it tougher for guests to make use of the islands. They beneficial a brand new, shorter bridge over the unstable Oregon Inlet that opened in 2019 at a price of $250 million {dollars}. A 3rd bridge, constructed after a hurricane minimize an inlet by an particularly weak part of Pea Island, price hundreds of thousands extra.

Outten stated the up-front expense of constructing one lengthy bridge to bypass a number of sizzling spots can be prohibitive. It might be cheaper and sooner to unfold the price of a number of bridges over time, in impact creating an archipelago akin to the Florida Keys. “The concept is to troubleshoot options,” he stated, “then to go to DOT and our federal legislators in Washington and inform them we have to do one thing.”

Geologist Stanley Riggs, who for many years was based mostly at East Carolina College and has most likely studied the Outer Banks greater than some other researcher, stated even a sequence of quick bridges might not be sufficient with rising sea ranges and extra highly effective storms in our overheated future. “I don’t see how this ends effectively,” he stated. “They’re making an attempt to protect a coastal economic system that was constructed on a pile of shifting sand and in the long term has a excessive chance of failure.”